30 July 2020

Japanese Verb Conjugation 101

(This article was reviewed and edited by native Japanese speakers to ensure accuracy.)

Why do Japanese verbs conjugate?

Japanese verbs conjugate to express tenses, to connect with other phrases, and to show various nuances. Compared to other languages, Japanese conjugation types can be a bit more complicated. There are many different verb forms as well as polite forms. The conjugations can even be combined together!

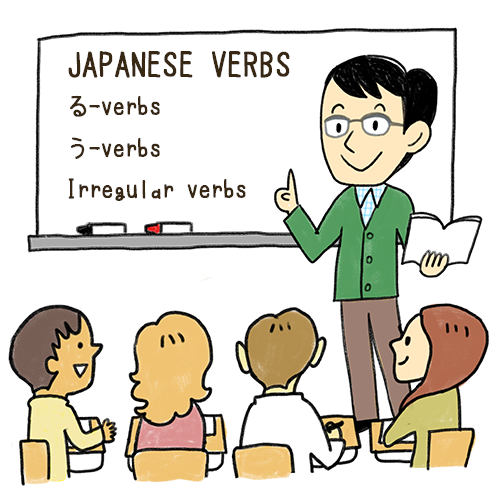

Ru-verbs, U-verbs, and Irregular Verbs

Verbs in Japanese can primarily be categorized into two types: ru-verbs and u-verbs. This refers to a verb’s dictionary form. It’s important to know these two types to understand conjugation rules.

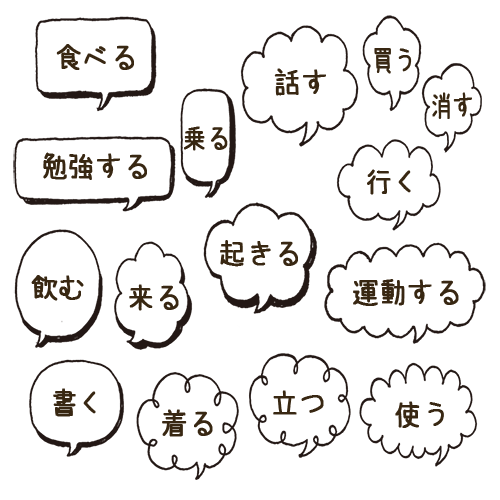

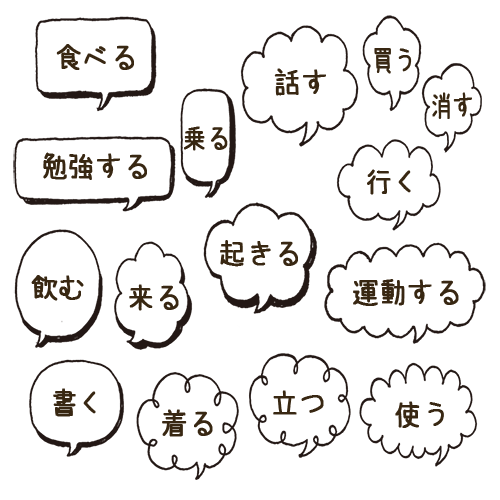

Ru-verbs

Ru-verbs are those that end in る, that have either i or e vowel sounds before the る.

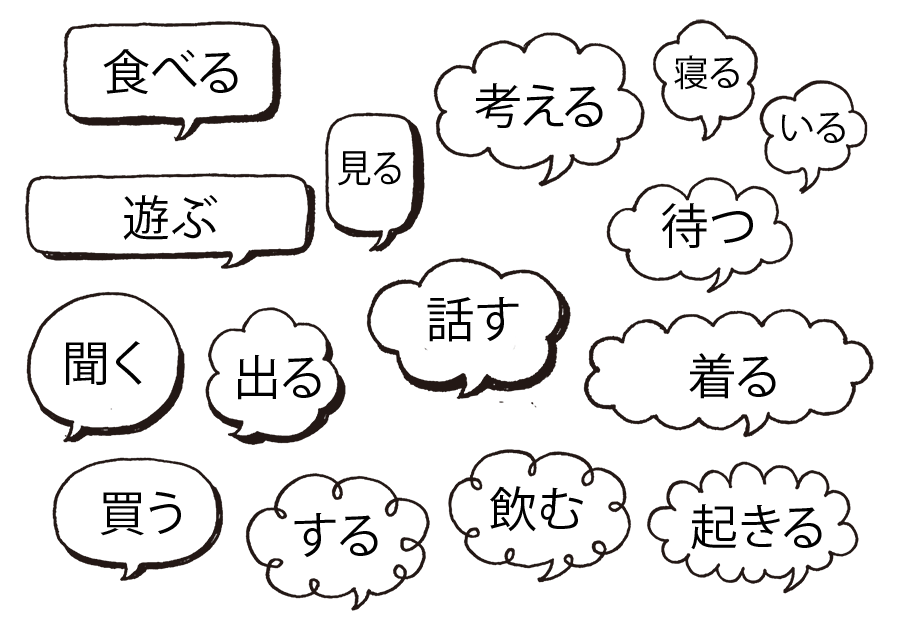

Some examples include 食べる(taberu), 着る(kiru), or 寝る(neru).

U-verbs

U-verbs are any verbs which end in u, which is not a ru-verb. This can be any verb ending like う(u), つ(tsu), む(mu), etc… This also includes verbs ending in る that don’t have an eru or iru ending.

Some examples of u-verbs are 立つ(tatsu), 学ぶ(manabu), 飲む(nomu), and 分かる(wakaru).

U-verbs that look like Ru-verbs

Unfortunately, there are exceptions to the rules and some u-verbs look like ru-verbs. This means that some eru and iru ending verbs are part of u-verbs. These simply have to be memorized.

Here are some common u-verbs that look like ru-verbs: しゃべる(shaberu), 帰る(kaeru), 知る(shiru), 入る(hairu), and 走る(hashiru).

Irregular verbs

There are two main irregular verbs in Japanese that don’t belong in ru-verbs or u-verbs. These are する(suru) and くる(kuru).

Polite and Casual Form

Most verb conjugations have a polite and casual form. Japanese is a language that values politeness. Depending on who you are talking to, it’s important to create different nuances in speech and writing. Navigating the polite and casual form in verb conjugations can help to express politeness or familiarity.

The polite form should be used if talking to those of higher social hierarchy, strangers, or older people. The casual form can be used with friends, family, and those of lower social hierarchy. Understanding when to use polite and casual form is best learned from interacting and observing native Japanese speakers.

Dictionary Form and Present Tense

The dictionary form of verbs is the casual present tense of a verb. As the name suggests, it is what can be found in dictionaries to look up verbs. This form is casual and you would only use it with friends and family. All dictionary form verbs end with the u-vowel.

An important thing to note about Japanese present tense is that it can also be used as the future tense.

Here are some examples of the dictionary form or casual present tense:

すしを食べる

Sushi o taberu

I eat sushi

お茶を飲む

Ocha o nomu

I drink tea

In spoken casual Japanese, particles are often dropped. It’s also common to answer by repeating the verb if someone asks you a question. This is because verbs don’t change based on the person it applies to. For example, “I eat” is the same as “she eats” in Japanese.

すし食べる?

Sushi taberu?

Do you want to eat sushi?

食べる。

Taberu.

(yes) I (want to) eat.

Since there’s no future tense, the dictionary form can apply to both present and future. The only way to figure out the tense is through context.

明日、学校行く。

Ashita, gakkou iku.

Tomorrow, I will go to school.

Negative Casual Present Tense:

To conjugate ru-verbs to the negative casual present tense you simply need to drop the る and add ない.

すしを食べる → すしを食べない

Sushi o taberu → Sushi o tabenai

I eat sushi → I don’t eat sushi

For u-verbs it’s easier to look at the romaji to change to the negative form. You need to drop the u and add anai to the end. If you prefer to conjugate with Japanese characters, you can also look at the hiragana ending of the u-verb and change it to the first hiragana in the same row, with an added ない.

お茶を飲む → お茶を飲まない

Ocha o nomu → Ocha o nomanai

I drink tea → I don’t drink tea

For irregular verbs, they don’t follow any rules and can only be memorized. They will change to the negative as follows:

くる → こない

kuru → konai

I come → I don’t come

する → しない

suru → shinai

I do → I don’t do

There is a special rule for verbs which end in う. They will change as if there is a w in front of the u.

買う → 買わない

ka(w)u → kawanai

I buy → I don’t buy

Here is an example of the casual negative present tense being used as the future tense. As discussed earlier, knowing if it is present or future tense relies only on the context.

明日学校行かない。

Ashita gakkou ikanai.

Tomorrow I won’t go to school.

This form can also be used as a way to make suggestions. You can make a suggestion by making it a question.

今日すし食べない?

Kyou sushi tabenai?

Do you want to eat sushi today?

To answer this question, you can use the negative and affirmative casual present tense.

yes: 食べる (taberu)

no: 食べない (tabenai)

Polite Present Tense

The polite present tense can be made by adding ます and ません. This is the form you should normally use unless with close friends, family, and those of lower social hierarchy.

For ru-verbs you only need to drop the る and add ます or ません(the negative form).

すしを食べる → すしを食べます

Sushi o taberu → Sushi o tabemasu

I eat sushi → I eat sushi (polite form)

すしを食べる → すしを食べません

Sushi o taberu → Sushi o tabemasen

I eat sushi → I don’t eat sushi (polite form)

For u-verbs you should drop the u and add imasu or imasen. If you prefer to conjugate with the Japanese characters, you should look at the hiragana of the verb ending and change it to the second hiragana in the same row. Then, add ます or ません at the end.

お茶を飲む → お茶を飲みます

Ocha o nomu → Ocha o nomimasu

I drink tea → I drink tea (polite form)

お茶を飲む → お茶を飲みません

Ocha o nomu → Ocha o nomimasen

I drink tea → I don’t drink tea (polite form)

The irregular verbs change to the polite form in the following ways:

する → します(affirmative)/しません(negative)

suru → shimasu/shimasen

くる → きます(affirmative)/きません(negative)

kuru → kimasu/kimasen

To make it a polite question, you can add か after the ます.

すし食べますか?

Sushi tabemasuka?

Would you like to eat sushi?

yes: 食べます (tabemasu)

no: 食べません (tabemasen)

To make it a suggestion, you can use the negative polite form and add か. It’s a softer nuance than adding か to the affirmative polite form.

一緒に食べませんか?

Issho ni tabemasenka?

Would you like to eat together?

ず-form

This is a useful conjugation that works on the negative casual present tense verb. You can take off the ない and replace it with ず.

食べない → 食べず

tabenai → tabezu

飲まない → 飲まず

nomanai → nomazu

The irregular verbs changes as follows:

する → せず

suru → sezu

くる → こず

kuru → kozu

This form doesn’t appear by itself and connects with other verbs. It can be used to make phrases that indicate that an action was done without doing the other action. In most cases it’s followed by に to make the phrase sound smoother.

朝ごはんを食べずに会社に行った。

Asagohan o tabezu ni kaisha ni itta.

I went to work without eating breakfast.

お茶を飲まずに会社に行った。

Ocha o nomazu ni kaisha ni itta.

I went to work without drinking tea.

Past Tense

Casual Past Tense

The casual past tense, which is also sometimes called ta-form, ends in た or だ. The negative form has the ending なかった.

For ru-verbs it is an easy conjugation where you drop the る and add た.

すしを食べる → すしを食べた

Sushi o taberu → Sushi o tabeta

I eat sushi → I ate sushi

For u-verbs there are more rules. う(u), つ(tsu), and る(ru) ending verbs will change to った(tta). む(mu), ぬ(nu), and ぶ(bu) ending verbs will change to んだ(nda). く(ku) changes to いた(ita), ぐ(gu) changes to いだ(ida), and す(su) changes to した(shita).

In the case of 飲む, it will change to んだ.

お茶を飲む → お茶を飲んだ

Ocha o nomu → Ocha o nonda

I drink tea → I drank tea

The irregular verbs follow their own rules:

くる → きた

kuru → kita

する → した

suru → shita

You can also form questions with the casual past tense by adding a question mark.

昨日、すし食べた?

Kinou, sushi tabeta?

Did you eat sushi yesterday?

Negative form

The negative form of the casual past tense has the same rule for all verb types. Take the ない form of the verb and replace ない with なかった. The nai-form of the verb is the negative casual present tense (negative version of the dictionary form).

すしを食べない → すしを食べなかった

Sushi o tabenai → Sushi o tabenakatta

I don’t eat sushi → I didn’t eat sushi

お茶を飲まない → お茶を飲まなかった

Ocha o nomanai → Ocha o nomanakatta

I don’t drink tea → I didn’t drink tea

昨日、すし食べなかった。

Kinou, sushi tabenakatta.

Yesterday, I didn’t eat sushi.

Polite Past Tense

To form the polite past tense you can take the polite present tense, and replace the ます ending with ました.

すしを食べます → すしを食べました

Sushi o tabemasu → Sushi o tabemashita

I eat sushi (polite form) → I ate sushi (polite form)

お茶を飲みます → お茶を飲みました

Ocha o nomimasu → Ocha o nomimashita

I drink tea (polite form) → I drank tea (polite form)

The polite past tense can also become a question by adding か. Unlike in present tense, this only applies to the affirmative and not the negative form.

昨日、すしたべましたか?

Kinou, sushi tabemashitaka?

Did you eat sushi yesterday? (polite form)

Negative form

The negative form of the polite past tense can be made by adding でした to the negative polite present tense.

すしを食べません → すしを食べませんでした

Sushi o tabemasen → Sushi o tabemasendeshita

I don’t eat sushi (polite form) → I didn’t eat sushi (polite form)

お茶を飲みません → お茶を飲みませんでした

Ocha o nomimasen → Ocha o nomimasendeshita

I don’t drink tea (polite form) → I didn’t drink tea (polite form)

昨日は学校に行きませんでした。

Kinou wa gakkou ni ikimasendeshita.

I didn’t go to school yesterday (polite form)

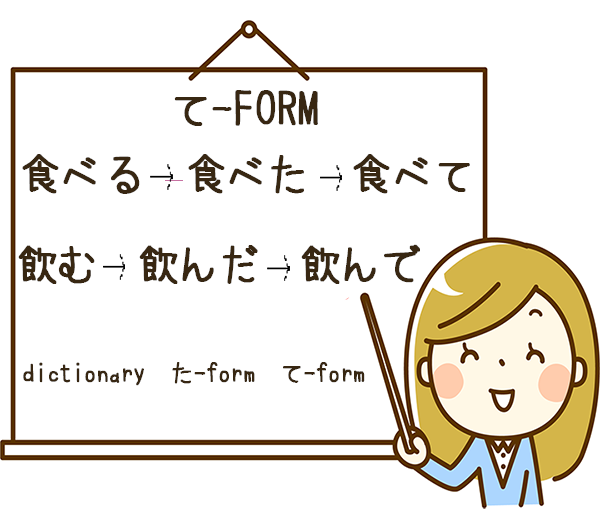

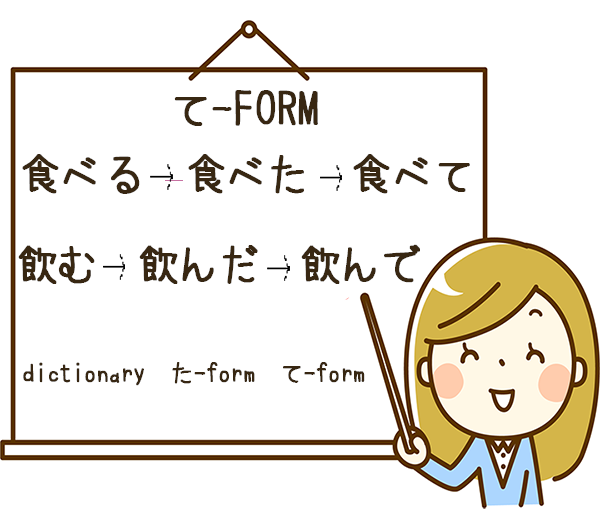

Te-form

This form is useful for making requests and connecting sentences. If you already know the past tense, it follows similar rules.

Here is how to form the causal te-form:

Any verb which ends in た in the past tense, changes to て.

すしを食べた → すしを食べて

Sushi o tabeta → Sushi o tabete

I ate sushi → Please eat sushi

Verbs that end in だ in the past tense, will change to で.

お茶を飲んだ → お茶を飲んで

Ocha o nonda → Ocha o nonde

I drank tea → Please drink tea

The negative and polite te-forms follow the same rules regardless of verb type. The negative te-form can be made using the negative dictionary form with an added で.

すし食べない → すし食べないで!

Sushi tabenai → sushi tabenaide!

I don’t eat sush→ Don’t eat sushi!

For the polite form, you can create it by adding ください to the te-form.

すしを食べて → すしを食べてください

Sushi o tabete → Sushi o tabetekudasai

Please eat sushi → Please eat sushi (polite form)

すしを食べないで → すしを食べないでください。

Sushi o tabenaide → Sushi o tabenaidekudasai.

Don’t eat sushi → Please don’t eat sushi (polite form)

In the previous examples, the te-form was at the end of the phrase. In these cases it acts to make a request.

If the te-form is in the middle of the sentence it usually connects phrases and verbs together.

すし食べてみる?

Sushi tabete miru?

Do you want to try eating sushi?

すし食べていく?

Sushi tabete iku?

Do you want to go eat sushi?

Te-form can also work to connect a series of actions. It acts as the word “then” in English.

昨日会社に行って仕事した。

Kinou kaisha ni itte shigoto shita.

Yesterday, I went to my company and (then) I worked.

よう、しょう form

This is also called the volitional form and expresses an intention or thought about doing something (if talking about yourself). It can also mean something similar to “let’s” or “shall we” in English if it includes other people. The ending (よ)う is the informal form and しょう is the polite form.

Casual Form

Ru-verbs

For ru-verbs, the casual form can be made by dropping the る from the dictionary form and adding よう.

すしを食べる → すしを食べよう

Sushi o taberu → Sushi o tabeyou

I eat sushi → Let’s eat sushi

U-verbs

For u-verbs, the informal form is made by dropping the u of the dictionary form and adding ou. If looking at the Japanese characters, take the last hiragana of the dictionary form, and change it to the last hiragana in the same row. Then simply add う to the end.

お茶を飲む → お茶を飲もう

Ocha o nomu → Ocha o nomou

I drink tea → let’s drink tea

For irregular verbs, they change in the following manner:

くる → こよう

kuru → koyou

する → しよう

suru → shiyou

さ、仕事しよう。

Sa, shigoto shiyou.

I think I’ll work (now).

If you add よ, it can be clear that you are talking to someone else and not about yourself. This is usually a childish or feminine way of speech but it can add a nuance that is more insistent.

すし食べようよ。

Sushi tabeyouyo.

Let’s eat sushi.

Polite

For the polite form, take the polite present tense and drop the す. Then, replace that with しょう. This works with all verb types.

すしを食べます → すしを食べましょう

Sushi o tabemasu → Sushi o tabemashou

I eat sushi (polite form) → let’s eat sushi (polite form)

お茶を飲みます → お茶を飲みましょう

Ocha o nomimasu → Ocha o nomimashou

I drink tea (polite form) → let’s drink tea (polite form)

仕事に戻りましょう。

Shigoto ni modorimashou.

Let’s return to work.

よ can also be added to the polite form to be more insistent. Unlike in the casual form, this way of speech sounds feminine but not childish.

早く行きましょうよ。

Hayaku ikimashou yo.

Let’s go quickly.

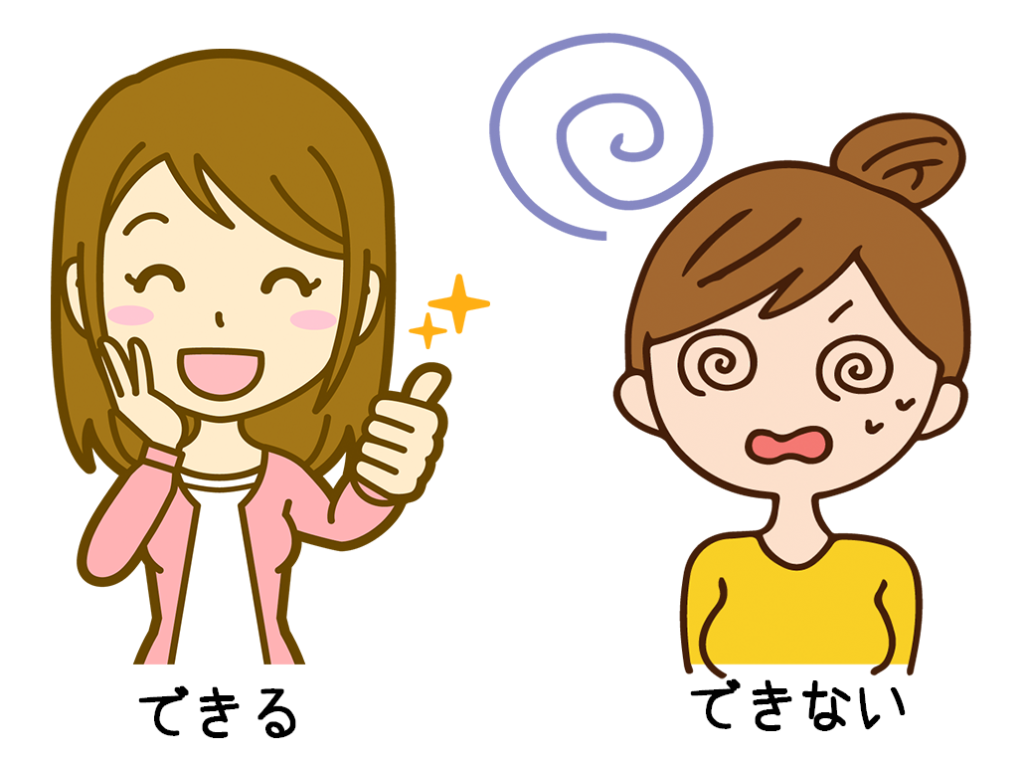

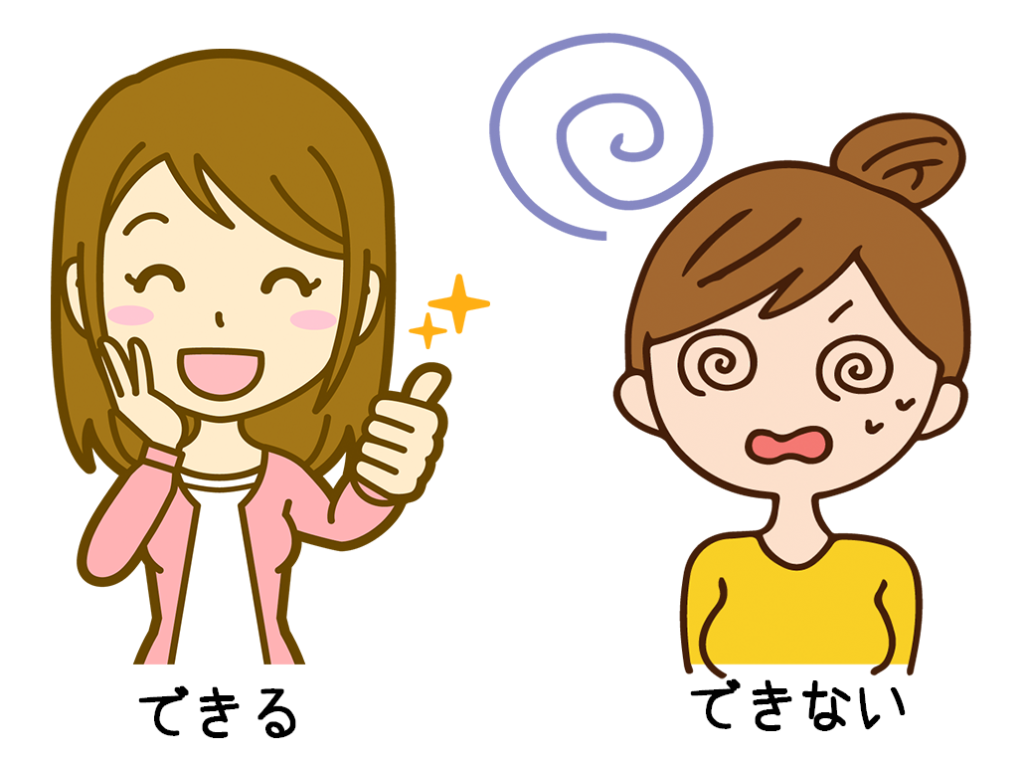

Potential Form

This form can be used to express the ability to do something. It is similar to “can” and “can not” in English.

Ru-verbs

The casual potential form can be made by dropping the る and adding (ら)れる or (ら)れない. The ら is often taken out to be smoother in daily speech and writing. Notice that the を preceding the dictionary form must change to が when changing to potential form.

すしを食べる → すしが食べ(ら)れる or すしが食べ(ら)れない

Sushi o taberu → Sushi ga taberareru or Sushi ga taberarenai

I eat sushi → I can eat sushi or I can’t eat sushi

U-verbs

To make the casual potential form with u-verbs, it’s necessary to drop the u and add eru or enai (negative form) to the end. If looking at the Japanese characters you can change the last hiragana of the verb to the fourth hiragana in the same row and add る or ない.

お茶を飲む → お茶が飲める or お茶が飲めない

Ocha o nomu → Ocha ga nomeru or Ocha ga nomenai

I drink tea → I can drink tea or I can’t drink tea

Irregular Verbs

These will change to the casual potential form as follows:

する → できる/できない

suru → dekiru/dekinai

くる → こられる/こられない

kuru → korareru/korarenai

Here are some examples of the casual potential form:

生の魚、食べれる?

Nama no sakana, tabereru?

Can you eat raw fish?

yes: 食べれる。(tabereru)

no: 食べれない。(taberenai)

忙しくて行けない。

Isogashikute ikenai.

I’m too busy and I can’t go.

Polite form

For the polite potential form, take the casual potential form and drop the る. Then, add ます or ません(negative form).

すしが食べられる → すしが食べられます or すしが食べられません

Sushi ga taberareru → Sushi ga taberaremasu or Sushi ga taberaremasen

I can eat sushi → I can eat sushi or I can’t eat sushi (polite form)

お茶が飲める → お茶が飲めます or お茶が飲めません

Ocha ga nomeru → Ocha ga nomemasu or Ocha nomemasen

I can drink tea → I can drink tea or I can’t drink tea (polite form)

Here are some example sentences:

今、会社に来れますか?

Ima, kaisha ni koremasuka?

Could you come to work now?

まだ会社に行けません。

Mada kaisha ni ikemasen.

I can’t go to work yet.

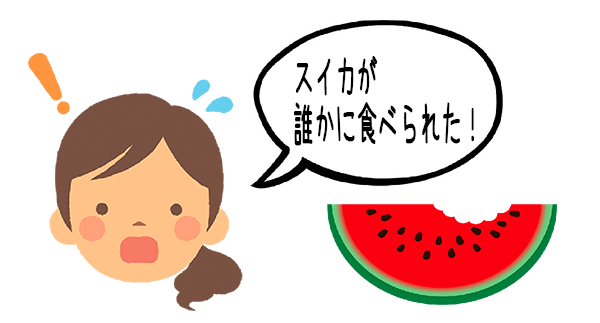

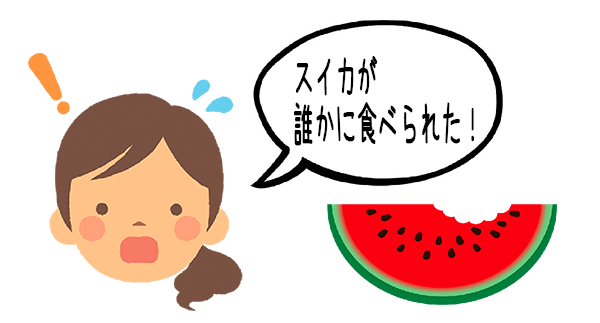

Passive

In Japanese, passive verbs can be used often. Unlike in English, the passive verb can also convey politeness because it doesn’t directly address the person that the action affects. It is especially common in formal writing.

Ru-verbs

In the passive form, ru-verbs look exactly the same as the potential form. However, make sure not to take out ら in the passive form of the verb. For the passive verb to work there must be an object in the beginning of the sentence.

熊に食べられる。

Kuma ni taberareru.

I will get eaten by a bear.

熊に食べられない。

Kuma ni taberarenai.

I will not get eaten by a bear.

The polite form:

熊に食べられます。

Kuma ni taberaremasu.

I will get eaten by a bear. (polite form)

熊に食べられません。

Kuma ni taberaremasen.

I will not get eaten by a bear. (polite form)

U-verbs

These verbs change to passive form by taking the negative present tense, dropping ない, and adding れる or れない (negative form).

お財布を盗まない → お財布が盗まれる or お財布が盗まれない

Osaifu o nusumanai → Osaifu ga nusumareru or Osaifu ga nusumarenai

I don’t steal the wallet → the wallet will get stolen or the wallet won’t get stolen

Irregular verbs

For the irregular verbs, change to the passive in the following ways:

する → される

suru → sareru

くる → こられる

kuru → korareru

Polite form

To make the passive form polite, take the る from the informal passive form and add ます or ません (negative form).

お財布が盗まれる → お財布が盗まれます

Osaifu ga nusumareru → Osaifu ga nusumaremasu

The wallet will get stolen → The wallet will get stolen (polite form)

お財布が盗まれる → お財布が盗まれません

Osaifu ga nusumareru → Osaifu ga nusumaremasen

The wallet will get stolen → The wallet won’t get stolen (polite form)

Other uses

The passive form is often used in the past tense and when unwanted events occur. To make the passive form into past tense, conjugate the passive form as a ru-verb by adding た.

車に轢かれたの?大丈夫?

Kuruma ni hikaretano? Daijoubu?

You were run over by a car? Are you ok?

今日財布盗まれた。

Kyou osaifu nusumareta.

My wallet was stolen today.

今日財布盗まれました。

Kyou osaifu nusumaremashita.

My wallet was stolen today. (polite form)

Here are some examples of unwanted events where you might use the passive form.

去年、妻に死なれました。

Kyonen, tsuma ni shinaremashita.

Last year, my wife died (I didn’t want her to die).

友達に先に行かれた。

Tomodachi ni saki ni ikareta.

My friend went before me.

誰かにケーキ食べられた。

Dareka ni keeki taberareta.

The cake was eaten by someone (I didn’t want that to happen).

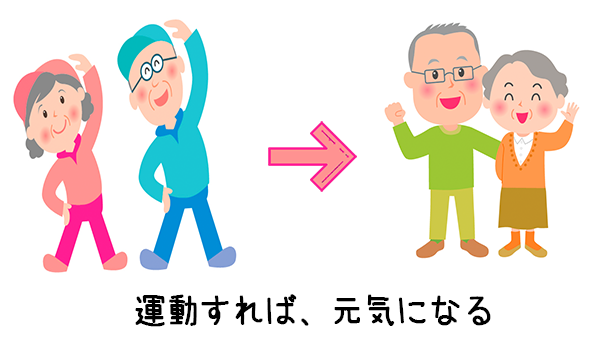

Conditional

This verb form can show “if” statements. The conjugation for the conditional form follows the same rule for all verb types.

For the affirmative, change the dictionary form of the verb by dropping the final u-vowel and adding e. Then, add ば.

食べる → 食べれば

taberu → tabereba

すしを食べれば、元気になる。

Sushi o tabereba genki ni naru.

If you eat sushi, you get energy.

飲む → 飲めば

nomu → nomeba

お茶を飲めば、病気にならない。

Ocha o nomeba byouki ni naranai.

If you drink tea, you won’t get sick.

For the negative, take the negative informal present tense (nai-form), remove ない and add なければ.

食べない → 食べなければ

tabenai → tabenakereba

すしを食べなければ、元気が出ない。

Sushi o tabenakereba, genki ga denai.

If you don’t eat sushi, you won’t get energy.

飲まない → 飲まなければ

nomanai → nomanakereba

お茶を飲まなければ、病気になる。

Ocha o nomanakereba, byouki ni naru.

If you don’t drink tea, you’ll get sick.

宿題すれば、ゲームしていいよ。

Shukudai sureba, geemu shite iiyo.

If you do your homework, you can play video games.

会社に来れば教えてあげます。

Kaisha ni kureba, oshiete agemasu.

If you come to the company, I will teach you.

Causative

The causative form of the verb can mean “to make” or” let” someone or something do an action. It’s important to see the context to know exactly what the phrase is trying to convey.

For ru-verbs, drop the る and add させる to create the causative.

すしを食べる → すしを食べさせる

Sushi o taberu → Sushi o tabesaseru

I eat sushi → I make (them) eat sushi

For u-verbs take out the last vowel u and add aseru.

お茶を飲む → お茶を飲ませる

Ocha o nomu → Ocha o nomaseru

I drink tea → I make (them) drink tea

Another way is to take the negative form, remove ない and add せる.

お茶を飲まない → お茶を飲ませる

Ocha o nomanai → Ocha o nomaseru

I drink tea → I make (them) drink tea

The two irregular verbs are conjugated as follows:

する → させる

suru → saseru

くる → 来させる

kuru → kosaseru

To make the negative and polite forms of the causative you can treat the conjugated causative verbs as ru-verbs. Remove る and add ない (negative), ます(polite affirmative), or ません(polite negative)。

食べさせる → 食べさせない/食べさせます/食べさせません

tabesaseru → tabesasenai/tabesasemasu/tabesasemasen

飲ませる → 飲ませない/飲ませます/飲ませません

nomaseru → nomasenai/nomasemasu/nomasemasen

Parents often use this to talk about making their kids do things.

子どもに野菜もっと食べさせる。

Kodomo ni yasai motto tabesaseru.

I make my children eat more vegetables.

すいません、静かにさせます。

Suimasen, shizuka ni sasemasu.

I’m sorry, I’ll make them be quiet.

Causative Passive

The causative passive is a combination of causative and passive verbs. Although it may seem confusing, it just means “to be made” to do something. To form the causative passive take the causative form and then conjugate it as a ru-verb into passive form.

すしを食べさせる → すしを食べさせられる

Sushi o tabesaseru → Sushi o tabesaserareru

I make (them) eat sushi → I am made to eat sushi

お茶を飲ませる → お茶を飲ませられる

Ocha o nomaseru → Ocha o nomaserareru

I make (them) drink tea → I am made to drink tea

To form the negative and polite forms, conjugate as a ru-verb in the present tense, using the endings ない(negative), ます(polite affirmative), or ません (polite negative).

食べさせられる → 食べさせられない/食べさせられます/食べさせられません

tabesaserareru → tabesaserarenai/tabesaseraremasu/tabesaseraremasen

飲ませられる → 飲ませられない/飲ませられます/飲ませられませんnomaserareru → nomaserarenai/nomaseraremasu/nomaseraremasen

Here are some example sentences uses the causative passive form:

いつも先生に教室の掃除をさせられます。

Itsumo sensei ni kyoushitsu no souji o saseraremasu.

My teacher always makes me clean the classroom.

友達に秘密を言わさせられた。

Tomodachi ni himitsu o iwasaserareta.

My friend made me say a secret.

Imperative

The command form in Japanese can be extremely rude and should never be used with someone who is of higher social hierarchy than you. However, it can be used to express anger or authority, and it can also be heard in anime and manga. In most cases, if you want to make a request, it’s better to use the te-form.

To create the imperative form for ru-verbs, drop the る and add ろ.

すしを食べる → すし食べろ!

Sushi o taberu → Sushi tabero!

I eat sushi → Eat sushi!

For u-verbs, change the last vowel to e.

お茶を飲む → お茶飲め!

Ocha o nomu → Ocha nome!

I drink tea → Drink tea!

The two irregular verbs conjugate as:

する → しろ

suru → shiro

くる → こい

kuru → koi

The negative imperative can be formed by adding a な to the dictionary form. This applies even to irregular verbs.

食べる → 食べるな!

Taberu → Taberuna!

to eat → Don’t eat!

飲む → 飲むな!

Nomu → Nomuna!

To drink → Don’t drink!

Conjugating further

Japanese verbs can be conjugated further and combined with different conjugations.

As seen earlier, the conditional passive is a great example of this. The conditional makes the verb function as a ru-verb so that it is simple to further conjugate it to passive.

As you study Japanese, you may notice more and more combined conjugations.

Here are some other examples of combining conjugations:

Potential form + past tense can be formed by taking the potential form and conjugating it to past tense as if it was a ru-verb.

すしが食べ(ら)れる →すしが 食べ(ら)れた

Sushi ga taberareru → Sushi ga taberareta

I can eat sushi → I could eat sushi

Passive + te-form can be formed by taking the passive form of the verb and conjugating it like a ru-verb in te-form.

食べられる → 食べられて

taberareru → taberarete

主人公が敵に食べられて死んだ。

Shujinkou ga teki ni taberarete shinda.

The main character was eaten by their enemy and died.

The causative passive can also further connect to the te-form. Here’s an example:

いつも宿題をやらさせられて辛い。

Itsumo shukudai o yarasaserarete tsurai.

It’s hard to always be made to do homework.

28 June 2020

What is te-form and When to Use It?

(This article was reviewed and edited by native Japanese speakers to ensure accuracy.)

The te-form can be an extremely useful and versatile grammar form. It is characterized by the ending て(te) or で(de).

What can be particularly confusing about this form is that there are many different uses and conjugation rules. It’s used for connecting different phrases and adjectives, showing a series of actions, and making requests. Hopefully, this article can clear up any confusion!

How to conjugate verbs to te-form

The first step to using te-form is to figure out how to form it. With verbs, you can either look at the past tense form or the dictionary form to determine its te-form. One important thing is that the te-form does not have any tense by itself. The tense is determined by the final verb that follows.

Conjugating using the past tense form

If you already know how to form the past tense, I’d recommend this method.

A verb ending of だ(da) in the past tense is replaced by で(de).

飲んだ → 飲んで

nonda → nonde

Verbs which end in た(ta) in the past tense changes to て(te).

食べた → 食べて

tabeta → tabete

Conjugating using the dictionary form

The more complex way to figure out the te-form is to use the dictionary form. Here’s how it works:

Ru-verbs or vowel stem verbs ending in る(ru) (also known as group 2 or ichidan verbs) will have the ending replaced by て(te). Not all ru-verbs follow this rule so it’s important to know the different verb groups.

食べる → 食べて

taberu → tabete

There are two irregular verbs ending in る(ru): する(suru), meaning “to do”, and くる(kuru), meaning “to come”. They are conjugated as follows.

する → して

suru → shite

来る → 来て

kuru → kite

U-verbs which end in う(u), つ(tsu), and る(ru), also known as group 1 or godan verbs, change to って(tte).

売る → 売って

uru → utte

買う → 買って

kau → katte

立つ → 立って

tatsu → tatte

Verbs ending in く(ku) and ぐ(gu) change to いて(ite) and いで(ide) respectively.

焼く → 焼いて

yaku → yaite

泳ぐ → 泳いで

oyogu → oyoide

Verbs ending in ぬ(nu), ぶ(bu), and む(mu) change to んで(nde).

死ぬ → 死んで

shinu → shinde

学ぶ → 学んで

manabu → manande

飲む → 飲んで

nomu → nonde

Verbs with an ending of す(su) change to して(shite).

話す → 話して

hanasu → hanashite

How to conjugate adjectives to te-form

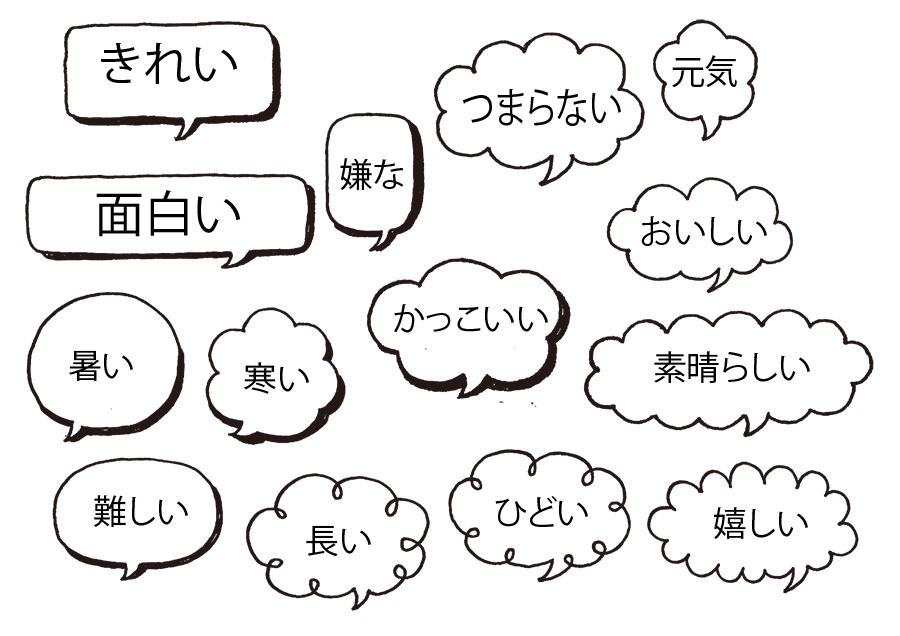

Adjectives can also be conjugated to te-form based on whether they are a な(na) or い(i) adjective. Na-adjectives are those that use な when describing something.

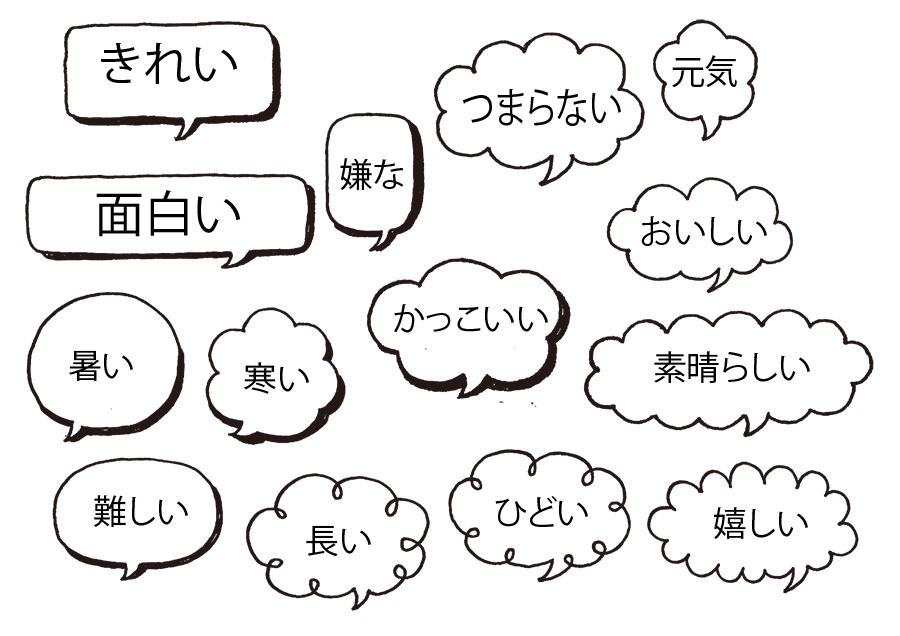

Examples include きれいな(kireina), 有名な(yuumeina), 小さな(chiisana). I-adjectives are those that end in い like 面白い(omoshiroi), 美味しい(oishii), or 美しい(utsukushii).

Na-adjectives change to で(de) and i-adjectives will change to くて(kute) in the te-form.

きれいな → きれいで

kireina → kireide

面白い → 面白くて

omoshiroi → omoshirokute

Negative te-form adjectives and verbs

Adjectives

There is only one form of the negative te-form of an adjective. It’s formed by taking the negative form of the adjective, dropping the ending い(i) and replacing it with くて(kute). For example:

na-adjective

きれいじゃない → きれいじゃなくて

kirei janai → kirei janakute

きれいではない → きれいではなくて

Kirei dewanai → kirei dewanakute

i-adjective

面白くない → 面白くなくて

omoshirokunai → omoshirokunakute

Verbs

These can have two forms, で(de) or くて(kute) in the negative te-form. で is used in situations where the te-form verb is connecting to another verb in a sentence pattern, or when making requests. They are formed by simply adding で to the negative form of the verb.

Here’s an example of how to form it:

歩かない → 歩かないで

arukanai → arukanaide

Here are some situational examples:

Connecting to another verb

走らないで運動しよう!

Hashiranai de undou shiyou!

Let’s exercise without running!

Making requests

走らないで!

Hashiranaide!

Don’t run!

くて(kute) typically connects verbs to adjectives and often implies a cause and effect. They are formed by dropping the い from the negative form of the verb and adding くて.

走らない → 走らなくて

hashiranai → hashiranakute

Situational examples:

Verb connecting to adjective

走らなくていい。

Hashiranakute ii.

You don’t have to run.

Cause and effect

勉強しなくて、先生に怒られた。

Benkyou shinakute, sensei ni okorareta.

I didn’t study so I was scolded by my teacher.

Using te-form verbs to connect sentence patterns

One of the primary uses of verbs in te-form is to connect to different sentence patterns. After creating the te-form with one verb, it can further connect to another verb or adjective.

An important thing to keep in mind is that all of these phrase endings also have a negative form. However, the negative form affects the verb in te-form, and not the ending verb. Here are some common ones:

~ている (te iru) and ~ていない (te inai)

This connects a verb to いる(iru), meaning “to be”. The negative form is 〜ていない. In English it is similar to the “ing” form. It expresses something that is continuously happening.

今、お昼食べている。

Ima, ohiru tabete iru.

I’m eating lunch right now.

今、お昼食べていない。

Ima, ohiru tabete inai.

I’m not eating lunch right now.

When forming these sentences, the い after て is often dropped so it is smoother.

今、お昼食べてる。

Ima, ohiru tabeteru.

I’m eating lunch right now.

今、お昼食べてない。

Ima, ohiru tabetenai.

I’m not eating lunch right now.

~てみる (te miru) and 〜てみない (te minai)

These two sentence patterns mean something like “to try”. The negative form is 〜てみない and can in certain cases means something similar to the positive form. Here are two examples:

宝くじ買ってみる?

Takarakuji katte miru?

Do you want to try buying a lottery ticket?

宝くじ買ってみない?

Takarakuji katte minai?

Why don’t we try buying a lottery ticket?

~ていく (te iku) and 〜ていかない (te ikanai)

This connects to the verb, いく(iku), which means “to go” and its negative form is 〜ていかない . The te-form verb that precedes the sentence ending is something you will or will not do before going.

ご飯作っていくよ。

Gohan tsukutte ikuyo.

I’ll make food before I go.

ご飯作っていかない。

Gohan tsukutte ikanai.

I won’t make food before I go.

~てくる (te kuru) and 〜てこない (te konai)

These sentence patterns connect to the verb くる(kuru), which means “to come”. However, it doesn’t really mean “to come” in this context, but more like “going” or “not going”. It also implies that you’ll come back to the original place after completing the action.

外で運動してくる。

Soto de undou shite kuru.

I’m going to run outside.

外で運動してこない。

Soto de undou shite konai.

I’m not going to run outside

〜てある(te aru) and 〜てない(te nai) to exist

This connects the verb ある(aru), meaning “to exist”, to the any te-form verb. In these contexts it means something like “have” and “have not”. It’s used when something has or hasn’t been done already.

In the first example sentence, 〜てある implies that the ice cream is still there and hasn’t been eaten yet.

アイスクリーム買ってある。

Aisukuriimu katte aru.

I’ve bought ice cream.

アイスクリーム買ってない。

Aisukuriimu katte nai.

I haven’t bought ice cream.

~ていい(te ii)

This is a unique sentence ending because it connects to an adjective. いい(ii) comes from the adjective 良い (yoi or ii). It means “it’s ok”. The negative form of this sentence ending is not commonly used because it sounds awkward.

お菓子買っていい?

Okashi katte ii?

Is it ok to buy sweets?

The negative te-form of the verb will typically use くて(kute) because it’s connecting to an adjective. However, it can also work with で(de)

お金、返さなくていいです。

Okane, kaesanakute ii desu.

It’s ok not to return the money.

お金、返さないでいいです。

Okane, kaesanaide ii desu.

It’s ok not to return the money.

Describes a series of action

The te-form can also be used when describing events that are unfolding. It can be used like the word “then” in English. It might seem strange to add “then” to every phrase in the sentence, but in Japanese it’s necessary to put the te-form to link them all together.

It’s important that all events or actions be listed chronologically. Also, the final phrase of the sentence is what determines the tense of the whole sentence.

今日は会社行って、帰りに服買って、晩ごはん食べてくる。

Kyou wa kaisha itte, kaeri ni fuku katte, ban gohan tabete kuru.

Today I will go to work, then buy clothes on the way back, and then I am going to eat dinner.

昨日、買い物行って服買ってきた。

Kinou, kaimono itte fuku katte kita.

Yesterday, I went shopping and then bought clothes.

Making a request

This is another common use of the te-form. Although te-form often links phrases together, in these situations it comes at the end of the sentence.

The informal version of making a request, can be made using the te-form verb at the end of the sentence.

早く学校に来て!

Hayaku gakkou ni kite!

Come to school quickly!

やめてよ!

Yamete yo!

Stop it!

To make it formal, you can add ください (kudasai) at the end. However, it’s important to know that this can still sound demanding and strong.

早く学校に来てください!

Hayaku gakkou ni kite kudasai!

Please come to school quickly!

As a reminder, in the negative te-form of a verb, always use で (de).

こっち来ないで!

Kocchi konaide!

Don’t come here!

こっち来ないでください!

Kocchi konaide kudasai!

Please don’t come here!

触らないで!

Sawaranaide!

Don’t touch!

触らないでください!

Sawaranaide kudasai!

Please don’t touch!

In polite situations, you may want to ask for something in a softer way. You can use the verbs もらう(morau) or いただく(itadaku). Both verbs mean something like “to recieve”, but it’s like adding “could” or “would” in English.

明日学校に来てもらえませんか?

Ashita gakkou ni kite moraemasen ka?

Could you come to school tomorrow?

明日学校に来ていただけませんか?

Ashita gakkou ni kite itadakemasen ka?

Could you come to school tomorrow?

明日学校に来てもらえると嬉しいんですけど。

Ashita gakkou ni kite moraeruto ureshiin desu kedo.

It would be nice if you could come to school tomorrow.

明日学校に来ていただけると嬉しいんですけど。

Ashita gakkou ni kite itadakeruto ureshiin desu kedo.

It would be nice if you could come to school tomorrow.

Adjectives

Te-form adjectives are used to connect to both adjectives and verbs.

Adjectives connecting to verbs will usually have a cause and effect pattern. It is similar to “so” in English.

テスト、難しくて落ちた。

Tesuto, muzukashikute ochita.

The test was hard so I failed.

It can also link adjectives together, acting like the “and” in English. However, unlike “and” it needs to be used with every adjective until the last adjective.

夜は暗くて怖い。

Yoru wa kurakute kowai.

The night is dark and scary.

鈴木さんは背が高くて、頭が良くて、面白い人です。

Suzuki-san wa se ga takakute, atama ga yokute, omoshiroi hito desu.

Suzuki-san is a tall, smart, and interesting person.

Many Japanese learners can confuse と(to) which links together objects. In this case, make sure not to write: 夜は暗いと怖い (incorrect)

Advice for learning and using te-form

Since there are many uses and conjugations for te-form, it can be difficult to learn. It can be a good start to use the guidelines and rules, but eventually, it might be better to memorize conjugations separately from the rules. Another tip would be to observe the te-form in written text and when listening to Japanese. This could help you to be more intuitive when figuring out how to form the phrases themselves.

4 June 2020

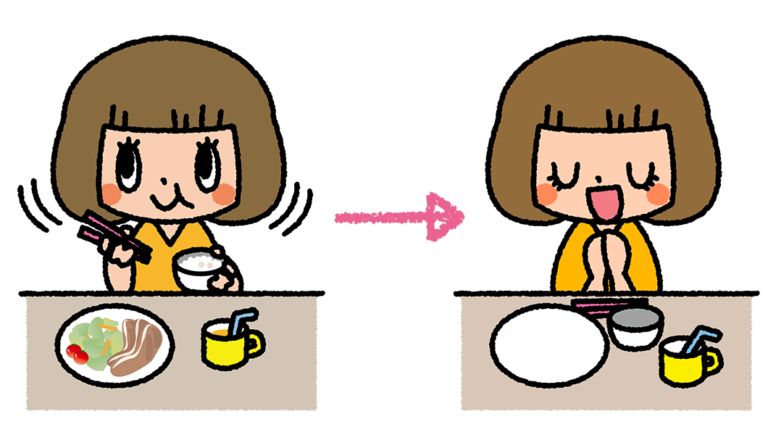

Itadakimasu! A Guide to Japanese Meal Time Words and Phrases

(This article was reviewed and edited by native Japanese speakers to ensure accuracy.)

Meal times are an important part of Japanese culture. Wide varieties of food are everywhere, especially in big cities. Even on Japanese T.V., you might notice there are more shows and segments related to cooking and food than other countries. Anime and manga also often feature storylines like becoming a professional chef or patissiere.

Food and meals are such a central part of the culture, that there tends to be many different words and phrases compared to English.

Basic meal words

The following words all mean “meal” in Japanese. These words can be used at any time of day, and it doesn’t specify the timing of the meal. Since Japanese has varying levels of formality in the language, there are differences in the politeness levels of these words.

ごはん – Gohan

This word, also written ご飯, literally means “rice” but it can also mean “meal”. In Japanese cuisine, rice is considered as the 主食(Shushoku) or “staple food”. Back in the day, most people ate meals that consisted of rice, soup, and side dishes. This is why the same word for “rice” is used for the word “meal”.

ごはん, is mainly used in casual Japanese with friends and family. Here are a few sentences where ごはん is used as the word “meal”:

ごはん何がいい?

Gohan nani ga ii?

What do you want to eat?

今日、ごはん外で食べてくる。

Kyou, gohan soto de tabete kuru.

I’m going to eat out today.

Here are also some situations where ごはん is used for the word “rice”:

パンとごはん、どっちが好き?

Pan to gohan, docchi ga suki?

Do you prefer bread or rice?

ごはん炊けた?

Gohan taketa?

Is the rice cooked?

食事 – Shokuji

This word for “meal” has a more formal and respectful image. The two kanji means “eat” (食) and “things” (事). It’s commonly used in polite situations or when referring to a fancier sit-down meal.

今度、食事でもどう?

Kondo, shokuji demo dou?

How about going for a meal next time?

食事の仕度しなきゃ。

Shokuji no shitaku shinakya.

I have to prepare the meal.

When using 食事 it becomes more polite if you add お. This can be especially useful when talking to someone who is higher in social status or hierarchy.

これからお食事でもいかがですか?

Korekara oshokuji demo ikaga desu ka?

Would you like to go for a meal?

飯 (メシ) – Meshi

This word also comes from the word “rice” and means “meal”. It is a very informal way of speaking and it’s normally used by men. It has a masculine nuance and it’s best to use it with those who are of lower or equal social status.

飯にしない?

Meshi ni shinai?

Shall we eat?

Breakfast

Similarly to the words for “meal”, the following words mean “breakfast” in various levels of formality. The word “morning”, 朝 (asa), is attached to each of the basic meal words to form the word “breakfast”.

朝ごはん – Asagohan

This word works similarly to the word ごはん except that it refers to breakfast. It is a casual way of saying breakfast.

朝ごはん食べる人?

Asagohan taberu hito?

Who wants breakfast?

朝食 – Choushoku

Like the word 食事, this is also a more formal way of saying breakfast. It’s often heard or used when eating out for breakfast, such as in hotels.

ホテルに朝食ついてる?

Hoteru ni choushoku tsuiteru?

Is there breakfast at the hotel?

朝食は一階になります。

Choushoku wa ikkai ni narimasu.

The breakfast is on the first floor.

朝飯 – Asameshi

This is the most informal version of the word “breakfast”. It is mostly used by men and functions like the word, 飯.

朝飯まだ?

Asameshi mada?

Is breakfast ready?

Lunch

There are many different ways of saying “lunch” in Japanese. It’s reflected by the fact that people might be out of the house during lunchtime; work, school, or dining out. Adding the word 昼 (hiru), or noon, to the words for “meal” can turn them into “lunch”.

昼ごはん – Hirugohan

This word for “lunch” can be directly translated as “noon rice”. As explained earlier, the word rice, ごはん, has become synonymous with the meaning for “meal” in Japanese. 昼ごはん is the word used more commonly among friends and family.

昼ごはんもう食べた?

Hirugohan mou tabeta?

Did you eat lunch yet?

昼食 – Chuushoku

This is a polite and more formal way of saying “lunch”. It may be used by event coordinators, hotels, or other service industries.

三ツ星レストランでの昼食となります。

Mitsuboshi resutoran de no chuushoku to narimasu.

Lunch will be served at a three-star restaurant.

昼食は隣の部屋に用意しております。

Chuushoku wa tonari no heya ni youi shite orimasu.

Lunch will be served in the room next door.

昼飯 – Hirumeshi

Because of the word 飯, this is the most informal form of saying “lunch”. It’s used mainly by men when talking to someone of equal or lower social status.

今日の昼飯どうする?

Kyou no hirumeshi dousuru?

What should we have for today’s lunch?

お昼 – Ohiru

This is the most versatile way of saying “lunch”. It simply adds an お, as a polite form, to the word 昼, or noon. It can casually be used among friends and family.

そろそろお昼にしましょうか。

Sorosoro ohiru ni shimashou ka.

Shall we have lunch soon.

お母さん、お昼まだ?

Okaasan, ohiru mada?

Mom, is it lunch yet?

It can even work in certain polite situations. For example, it would be possible to say this to your boss:

お昼はどうされますか?

Ohiru wa dou saremasu ka?

What is your lunch plan?

However, in service industries towards customers or in big events, it’s important to know that the word “lunch” would not be お昼, but 昼食.

ランチ – Ranchi

This is a borrowed word from English. It’s simply “lunch” written in katakana. Japanese people feel that words from other languages are more hip or trendy. In the case of the word ランチ, women and girls might use this word to sound more stylish. Also, many cafes and restaurants will display this word to appear more attractive.

ランチ行かない?

Ranchi ikanai?

Do you want to go for lunch?

ランチはじめました。

Ranchi hajimemashita.

We started serving lunch.

お弁当 – Obento

This is a very important part of Japanese culture and refers to a “packaged lunch”.

お弁当 usually consists of rice and side dishes in a container. It has a long history and possibly originates from the 12th century. It is also said to come from the word “convenient” in Chinese.

These days, お弁当 not only comes in the form of rice and side dishes, but there are also packaged sandwiches or cute character お弁当 called キャラ弁 (kyaraben).

お弁当 are either made at home or bought outside in convenience stores or train stations.

美味しそうなお弁当だね。

Oishisou na obento da ne.

That packaged lunch looks delicious.

今日はお弁当いらない。

Kyou wa obento iranai.

I don’t need a packaged lunch today.

給食 – Kyuushoku

This means “school lunch” and is a combination of 給 (kyuu), meaning “to give out” and 食 (shoku), meaning “to eat”.

It is not simply a school lunch, but it consists of a balanced and fresh-cooked meal. The students help out with serving the meal. It also helps teach young students about nutrition and to be grateful for the food.

今日の給食何だった?

Kyou no kyuushoku nan datta?

What was today’s school lunch?

Snack/afternoon tea

おやつ – Oyatsu

This is one of the most casual and childish ways of saying “snack”. Parents will often use this word with their children. There is a phrase in Japanese called 三時のおやつ (Sanji no oyatsu), which means “three o’clock snack”. Japanese children often associate snack time being around 3pm.

今日のおやつ何?

Kyou no oyatsu nani?

What’s today’s snack?

おやつの時間が楽しみ!

Oyatsu no jikan ga tanoshimi!

I’m excited for snack time!

軽食 – Keishoku

This refers to a light meal or snack that might be given out at meetings, airplane flights, or when working over-time. It’s a word that is used in formal situations that signifies that the food will not be a meal but something like a snack.

軽食をご用意しております。

Keishoku o goyoui shite orimasu.

We have prepared a light meal.

お茶 – Ocha

In English, we might be used to saying “let’s grab a coffee” or “ do you want to go to a cafe?”. However, in Japanese, the culture of tea is so important that all of these might be expressed with the term お茶, meaning “tea”. It doesn’t necessarily mean only “tea” but it could be coffee, snacks, cake, tea, or other traditional sweets. You can use it to ask people to come for afternoon tea or going out to a cafe.

今度お茶しない?

Kondo ocha shinai?

Do you want to go for tea sometime?

Dinner

Similarly to the words for lunch, the words for dinner are also mostly compound words made of a meal word and the time it is eaten. However, there are more words for evening or night in Japanese like 夜, 晩, 夕 which can be confusing.

晩ごはん – Bangohan

This is another compound word with ごはん combined with 晩(ban) which means “night”. This refers to the time period after the sun sets when most people are still awake. It is used casually among friends and family.

晩ごはん何がいい?

Bangohan nani ga ii?

What do you want for dinner?

晩飯 – Banmeshi

This word replaces ごはん with 飯 which makes it much more informal than 晩ごはん. Like all 飯 words, it is mostly used by men.

晩飯食いに行こう。

Banmeshi kui ni ikou.

Let’s go eat dinner.

夕食 – Yuushoku

This word combines 夕(yuu) which means “evening” or the time that the sun is about to set, and 食(eat). Since it is a word with 食, it is a formal and polite form of saying “dinner”.

夕食はホテルになります。

Yuushoku wa hoteru ni narimasu.

Dinner will be at the hotel.

ディナー – Dinaa

Like the word ランチ, this word is also a borrowed English word. It simply means “dinner” and written in katakana. It gives off a trendy and western feel, so many posh restaurants will use this word. It can also be used when you want to talk about a nice sit-down dinner.

ディナーはご予約をおすすめします。

Dinaa wa goyoyaku o osusume shimasu.

Reservations are recommended for dinner.

夜ごはん – Yorugohan

This is a word that can also be interchangeable with 晩ごはん or 夕ごはん. 夜 in 夜ごはん technically means late-night, but in this context all of the dinner ごはん words are exchangeable. It’s important not to confuse it with 夜食 which means “late-night snack”.

夜ごはん何がいい?

Yorugohan nani ga ii?

What do you want for dinner?

夕ごはん – Yuugohan

This word uses 夕 in front of ごはん, and would technically refer to an early dinner when the sun is setting. However, it can basically be used interchangably 晩ごはん or 夜ごはん.

夕ごはん何がいい?

Yuugohan nani ga ii?

What do you want for dinner?

夜食 – Yashoku

This word refers to a small late-night meal or snack and it would not be considered dinner. It would be used in situations when you stay up late enough to get hungry again. The difference between 夕食 and 夜食 is that the kanji, 夜(yoru), refers to the time of day when people are asleep.

夜食にカップ麺食べた。

Yashoku ni kappumen tabeta.

I ate cup noodles for my late-night snack.

Meal time verbs:

There are many verbs that are related to meal times, and some may not be as intuitive from an English-speaking perspective. It can be tricky because they can change their meaning when used in different contexts.

食べる – Taberu

One of the most straightforward verbs, this simply means “to eat”.

何食べる?

Nani taberu?

What do you want to eat?

まだ食べてないの?

Mada tabete naino?

Have you eaten yet?

It’s important to note that the words ごはん, 朝ごはん, 昼ごはん, and 夜ごはん will usually pair with 食べる, when referring to eating these meals.

もう朝ごはん食べた?

Mou asagohan tabeta?

Have you already eaten breakfast?

食べる can also sometimes be used as 食う (Kuu), which is the form that would most likely go with the words 飯, 朝飯, 昼飯, 晩飯. It is a very informal way of saying “to eat”, that men may use.

もう夕飯食ったよ。

Mou yuumeshi kutta yo.

I already ate dinner.

取る – Toru

This verb means “to take”. In a meal time context, it is a more polite way of saying “to eat” or “to have” a meal. It usually accompanies the words 食事、朝食、昼食、or any meal word with 食. Because this is more formal, it would be weird to use it with words like ごはん or 飯.

行く前に軽く昼食とろうか。

Iku mae ni karuku chuushoku torouka?

Shall we have a light lunch before we go?

残す – Nokosu

In Japanese culture, it can be considered rude to leave food on your plate.

This verb, which means “to leave”, can be used to talk about leaving food. It’s something that parents and teachers often tell children.

残さないで食べましょう。

Nokosanai de tabe mashou.

Let’s eat without leaving food.

出る – Deru

This verb means to “put out” or “go out”, but means “to serve” in a meal time context. You can use this verb to talk about food that you will serve someone or food that was served to you.

昼食はラーメンが出た。

Chuushoku wa raamen ga deta.

Ramen was served for lunch.

盛る – Moru

This can be an interesting verb because it also means “to serve”, “to plate”, or “to pile something”. It’s used when talking about foods that can be “piled” onto a plate or bowl.

どれくらいごはん盛ればいい?

Dorekurai gohan moreba ii?

How much rice should I serve?

It’s especially useful when asking for larger portions of rice or other dishes. The large portion would be called 大盛り(oomori) and can be an option in some restaurants and eateries.

ごはん大盛りでお願いします。

Gohan oomori de onegaishimasu.

I would like a large portion of rice, please.

飲む – Nomu

This is the verb “to drink”. It can be used similarly to how we use the word “drink” in English. The same verb can be used for drinking alcohol or going to a bar.

何飲む?

Nani nomu?

What do you want to drink?

今日、飲みに行かない?

Kyou, nomi ni ikanai?

Do you want to go for a drink today?

Other mealtime phrases and words

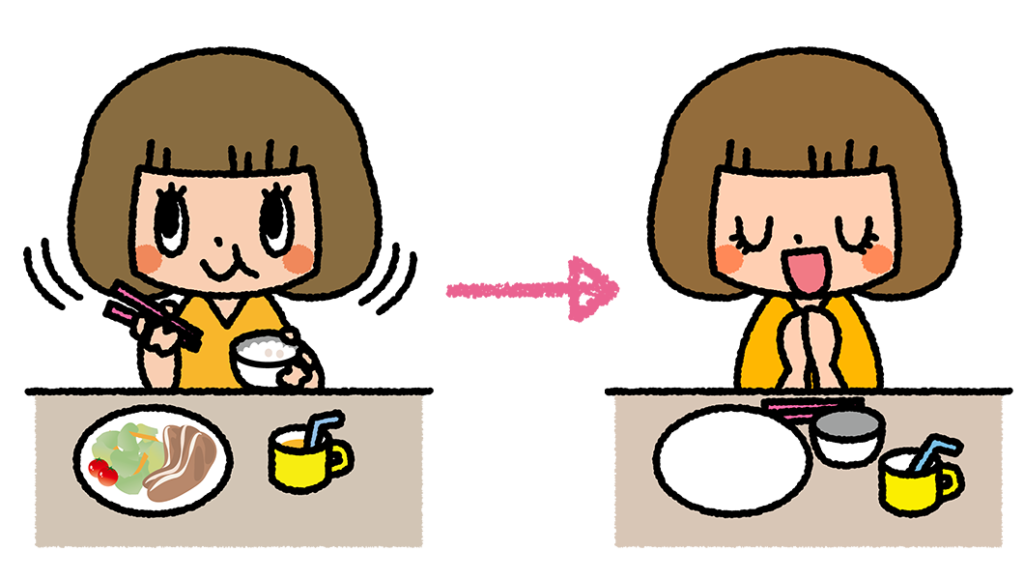

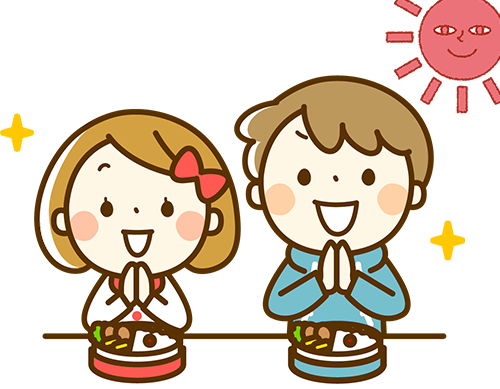

いただきます – Itadakimasu

This is a phrase that is used before eating a meal. It can show appreciation for the food and the person who made it. It’s common to put your hands together and say いただきます.

The phrase itself comes from いただく, which is a polite way to say “to take” or “to have”. It means something like “I will take/have this food” and can be comparable to “bon appétit” or “let’s eat”.

It’s common for Japanese people to say it before every meal, especially when they’re eating with other people. If you are invited, you should most definitely say this before eating.

今日のお昼美味しそう。いただきます!

Kyou no ohiru oishisou. Itadakimasu!

Today’s lunch looks delicious. Bon appétit!

めしあがれ – Meshiagare

The person who made the food might say めしあがれ and means something like “please eat”.

It’s usually a response to the phrase いただきます. It’s important to keep in mind that this phrase is usually directed to people of equal or lower social hierarchy. For example, adults might say this to children.

This phrase is much less common compared to いただきます in real life.

どうぞ、めしあがれ。

Douzo, meshiagare.

Go ahead, please eat.

ごちそうさまでした – Gochisousama deshita

After finishing the meal, it is polite to say ごちそうさまでした. ごちそう means a “delicious meal” or “feast”. The whole phrase means “it was a delicious meal” or “thank you for the meal”. It shows gratitude and appreciation to use this phrase.

If you are invited, it will be a polite thing to say when you finish eating. You can also say this when you leave.

ごちそうさまでした。とっても美味しかったです!

Gochisousama deshita. Tottemo oishikatta desu!

Thank you for the meal. It was very delicious!

お腹が空きました – Onaka ga sukimashita

In Japanese, the phrase for “being hungry” is お腹が空きました. It literally translates to “my stomach is empty”.

ランニングをしたらお腹が空きました。

Ranningu o shitara onaka ga sukimashita.

After running, I feel hungry.

あー、めっちゃお腹空いた。

Aa, meccha onaka suita.

Ah, I’m really hungry.

腹が減る – Hara ga heru

This is the informal version of お腹がすきました. In this phrase, it uses the verb 減る(heru) which means ”to decrease”. This way of speech is used mostly by men. It should also only be used with those of equal or lower social status than you.

腹減ったんだけど、ご飯まだ?

Hara hettandakedo, gohan mada?

I’m hungry, is the food ready?

お腹がいっぱいです – Onaka ga ippaidesu

This phrase also uses the stomach as the one determining the level of hunger. The phrase literally means “my stomach is full”. In Japanese, when referring to levels of hunger, you always have to talk about your stomach.

もう結構です。お腹がいっぱいです。

Mou kekkou desu. Onaka ga ippai desu.

It’s alright. I’m full.

もうお腹いっぱいだよ。

Mou onaka ippai da yo.

I’m already full.

腹いっぱい – Hara ippai

This is the informal version of お腹がいっぱいです. It’s mainly used by men and should only be used with those of equal or lower social status.

あー、すし腹いっぱい食いてー。

Aa, sushi hara ippai kuitee.

Ah, I want to eat sushi till I’m full.

おかわり – Okawari

This is the word for “seconds”, when you might want to get another helping of food. In Japanese, the concept of getting seconds might be more common than in the English speaking countries because of the tradition of eating rice and many side dishes. To balance out the salty flavors of the side dishes, it’s common to ask for a second helping.

ごはん、おかわり出来ますか?

Gohan, okawari dekimasuka?

Is it possible to have another helping of rice?

おかわり自由です。

Okawari jiyuu desu.

Free refills.

自炊 – Jisui

This is a word that means “to cook at home”. It comes from the kanji 自(yourself) and 炊(to cook). The kanji 炊, means “cook” but refers more to making rice.

This word represents the traditional Japanese eating style which assumed that if you are at home you would mainly eat rice and side dishes. Nowadays, it simply means that you cook at home and live alone.

いつも自炊してます。

Itsumo jisui shitemasu.

I always eat and cook by myself.

22 May 2020

Japanese Insults 101

(This article was reviewed and edited by native Japanese speakers to ensure accuracy.)

Insults can be one of the fun and interesting aspects of language learning. Once you begin to understand how insults work in a language it can also feel like you’re getting to know the culture and the people.

It should be no surprise that as Japanese is a relatively polite language, its insults are also a reflection of the culture. From the standards of other languages, Japanese insults are often much milder. Breaking social conventions is more important than the exact words that are used. Not using respectful language when you are supposed to, can be very insulting in Japan.

Basic Insult Words:

These are some basic words that may be used as insults.

One thing to keep in mind is that many of these words are considered childish, and are not taken too seriously in some situations. You may hear adults saying these words if they are in a serious fight.

That being said, it could be considered rude to use them so it’s best to be careful!

バカ (also 馬鹿) – Baka

This is one of the most basic insults and means “stupid”. It can be used for people and situations.

There are many uses and can range in meaning from a sign of concern, an angry insult, or a childish way to taunt someone.

When using towards a person, you can simply call the other person バカ. It’s also common to end the sentence with it.

割り込むなよ、バカ!

Warikomuna yo, baka!

Don’t cut in front, stupid!

よそ見してんじゃねえよ、バカ!

Yosomi shite n janee yo, baka!

Pay attention, stupid!

However, there are also a few ways to say it towards someone in a light-hearted way or with a sign of care.

If someone close to you talks about something they did that was a bit dumb, it’s possible to say the following phrases. In order to keep things fairly light-hearted, the other person must be of a lower status (ex. parent to child), younger or very close. It’s also important to keep the tone calm and not aggressive or angry.

バカじゃないの?

Baka ja nai no?

Are you stupid?

バカだな。

Baka da na.

You must be stupid.

Among children, this way of saying バカ might be common if they get in a small fight with each other:

けんたのバカ!

Kenta no baka!

Stupid Kenta!

The following two phrases with バカ can be used situationally. In a stupid situation you can talk about it with these phrases:

吹替版のアニメなんて馬鹿らしい。

Fukikaeban no anime nante bakarashii.

The dubbed version of the anime is so stupid.

そんなバカバカしいアニメまだ見てるの?

Sonna bakabakashii anime mada miteru no?

You’re still watching that stupid anime?

It’s also possible to comment on yourself, if you did something stupid. Here are a few ways:

私、バカみたい。

Watashi, baka mitai.

I feel stupid.

バカやっちゃった。

Baka yacchatta.

Oops, I did something stupid.

When actually angry and as an actual insult, バカ can also be used. However, it is mostly about the tone of the person saying it that would make the insult stronger.

バカ!

Baka!

Stupid!

The following two ways of saying バカ are probably more common in anime.

バカやろう!

Baka yarou!

You dummy!

バカもん!

Baka mon!

You dummy!

Another common バカ phrase that may appear in a certain anime is:

あんたバカ?

Anta baka?

Are you stupid?

Finally, there are a few other ways in which バカ can be used outside of simply meaning “stupid”.

バカにできない

Baka ni dekinai

It can’t be underestimated

親バカ

Oya baka

A parent who is stupidly overprotective of their child.

アホ – Aho

This word also means “stupid” and is more commonly used in the Kansai area, to replace バカ. It is basically the same as バカ but with a slightly softer nuance.

アホやな。

Aho yana.

That’s/You’re stupid.

アホくさ。

Aho kusa.

That’s stupid.

アホちゃう?

Aho chau?

Isn’t that/Are you stupid?

It’s also possible to simply call people アホ. Like バカ, it often appears at the ends of sentences.

割り込むなよ、アホ!

Warikomuna yo, aho!

Don’t cut in front, stupid!

よそ見してんじゃねえよ、アホ!

Yosomi shitenjanee yo, aho!

Pay attention, stupid!

クズ- Kuzu and カス- Kasu

These two words mean something like “worthless” and can be used toward another person to degrade them. It implies that the other person is less than human, garbage, or not worthy of respect.

クズやろう!

Kuzu yarou!

You piece of garbage!

このカス!

Kono kasu!

You scum!

くそ – Kuso

This is probably the closest insult that means “shit” in Japanese. However, it’s not as strong as the word “shit”. It can be used towards someone or when expressing disappointment.

くそ!負けた!

Kuso! Maketa!

Shit! I lost!

くそやろう!

Kuso yarou!

Piece of shit!

コラ – Kora

コラ is an interjection like “hey!” and has no specific meaning. It’s usually used to scold someone, as a way to call someone out, or when someone has wronged you.

It is not actually an insult, but it frequently appears together with insulting phrases. This can be added to the beginning or ends of phrases.

コラ!勝手に触るな!

Kora! Katte ni sawaruna!

Hey! Don’t you dare touch that!

何見てんじゃ、コラ!

Nani mitenja, kora!

Hey! What’re you looking at?

ふざけんなよ、コラ!

Fuzakenna yo, kora!

Hey! Don’t play around with me.

Annoyance Insults:

The following words can be used to express annoyance towards another person. It’s more common to hear these said by younger people. For example, an angsty teenager towards their parents might say some of these.

うるせぇ- Urusee

うるせぇ comes from うるさい which means “noisy”. However, when used in an angrier context it can turn into more of an insult like “shut up”.

うるせぇ!

Urusee!

Shut up!

うるせーなー!

Urusee naa!

Shut up (you are too noisy)!

お前ら、うるせぇぞ!

Omaera, urusee zo!

You guys, shut up!

うっせーんだよ!

Ussee n da yo!

Shut up! (this is more insisting)

だまれ – Damare

This is the command form of だまる, which means “to shut up”. It is probably the closest word to “shut up” in the English context.

だまれ!

Damare!

Shut up!

お前ら、ちょっとだまれよ。

Omaera, chotto damare yo.

You guys, shut up!

だまれ、バカ!

Damare, baka!

Shut up, stupid!

キモい – Kimoi

キモい comes from the shortened form of 気持ち悪い、which means “to feel sick” or “disgusting”. When used towards another person, it means you think the other person is gross, disgusting, or creepy.

お前、キモいんだけど。

Omae, kimoi n dakedo.

You’re gross.

あのおやじキモくない?

Ano oyaji kimokunai?

Isn’t that man creepy?

うざい – Uzai

This word is also a shortened form of a word, うざったい. It means “annoying” or “bothersome” and can be used towards other people.

お前うざいから消えろ。

Omae uzai kara kiero.

You’re annoying, go away.

あのジジイうざくね?

Ano jijii uzakune?

Isn’t that old man annoying?

Appearance Insults:

Just as in English, there are words that can be insulting based on appearance. Keep in mind that some of these words could be highly offensive and discriminatory if said to the wrong person.

ちび – Chibi – “Shorty”

だまれ、ちび!

Damare, chibi!

Shut up, shorty!

はげ- Hage – “Baldy”

うるさいんだよ、はげ!

Urusai n da yo, hage!

Shut up, baldy!

ブス- Busu – “Ugly”

キモいんだよ、ブス!

Kimoi n da yo, busu!

You’re gross, ugly!

デブ – Debu – “Fatty”

調子のってんじゃねーよ、デブ!

Choushi notte n janee yo, debu!

Don’t get cocky, fatty!

ババー – Babaa and ジジー – Jijii

These are the rude versions of the word for grandma and grandpa. Normally, we would say おばあさん (obaasan) おばあちゃん (obaachan), おじいさん (ojiisan), おじいちゃん (ojiichan). Even if the other person is not that old, it can be an insulting way to call someone.

ジジー、おせーよ!

Jijii, osee yo!

You old man, you’re so slow!

金返せよ、ババー!

Kane kaese yo, babaa!

Give me back the money, you old woman!

Appearance Insults towards yourself:

These insults are also sometimes used when talking about yourself to describe your own appearance.

デブになりたくないけどケーキ食べたい。

Debu ni naritakunai kedo keeki tabetai.

I don’t want to be a fatty, but I want to eat cake.

どうしよう、最近はげてきた。

Doushiyou, saikin hagetekita.

Oh no, I’m recently losing hair.

俺、ちびだけどバレーしたいんだ。

Ore, chibi dakedo baree shitai n da.

I’m short but I want to do volleyball.

Internet Insults

With the rise of social media, there are also insults that have popped up online. Keep a look out for some of these next time you’re reading some Japanese comment boards!

基地外 – Kichigai

Sometimes shortened to 基地 (kichi), it is a play on words and stands for 気違い(kichigai) which means a “crazy person”. To be more playful on the internet, they use a different kanji and the literal meaning of these kanji is “outside the fort”.

日本語でおk- Nihongo de ok

This can be used as an insult towards someone that makes no sense. It means “please use Japanese” as it can’t be understood. The reason why there is a “k” instead of hiragana is because when typing out “ok” in Japanese, the k remains in the Latin alphabet.

にわか – Niwaka

This is very common on the internet, especially in the anime community, and means something like “noob” or “newbie.” It’s used towards someone that doesn’t know much but suddenly appears to be knowledgeable about something.

For example, にわかファン (Niwaka fan) is a fan that became one recently and was not a die-hard fan from the beginning.

厨房 – Chuubou

This means 中坊 or “middle school boy” but it is using the kanji letters that mean “kitchen” to be playful. It is used towards someone who is immature.

DQN – Dokyun

This stands for “dokyun” and means someone that is unintellectual and has no common sense. It first appeared in a TV show title between 1994- 2002 目撃!ドキュン (Mokugeki Dokyun).

BBA/GGI – Babaa/Jijii

These two abbreviations appear frequently in social media. BBA stands for ババー and GGI stands for ジジー. As explained previously regarding ババー and ジジー it can be a rude and insulting way to call someone a grandpa or grandma regardless of age.

“You” as an Insult

Besides insult words that might describe someone, it can also be insulting to change the word “you” into something more informal and rude. By using these words, it can change the hierarchy of the speech so that the other person is of lower status. Here are several ways in which “you” can be said in an offensive way:

あんた – Anta

This word comes from a variation of あなた and it is not inherently rude. However, it is definitely an informal way of speech which should only be used towards someone equal or lower in status than you. In that sense, when used out of this context it immediately becomes insulting.

あんた分かってんの?

Anta wakatten no?

Do you not understand?

おまえ – Omae

おまえ can also be tricky because in some situations it is not insulting. It’s usually used with people who might be close friends or where the other person is of a lower status. At the same time, it inherently sounds rough and masculine, so not everybody uses this word. It can be rude even with close friends.

In English, it might be like the word “bro” or “dude”. However, outside of established social norms, it can easily come across as talking down to someone.

何してんの、おまえ?

Nani shite n no, omae?

What are you doing?

てめえ – Temee

Compared to the other two words, this one is the rudest and insulting way of saying “you”. That being said, it’s usually used quite frequently in anime. That’s because anime can be an exaggerated version of real life. In everyday situations, てめえ would likely be heard only in very heated and angry circumstances.

Unlike おまえ, people don’t usually use てめえ unless they want to sound insulting.

てめえが悪いんだよ!

Temee ga waruinda yo!

You’re the one that’s wrong!

やろう – Yarou

This word does not entirely mean “you” but is often used with other offensive words towards a person to mean something like “bastard”. When used as a “you” it can be used with この or “this”.

このやろう!

Kono yarou!

You bastard!

It can also be used to talk about someone that annoyed you. In that case, it would attach with あの or “that”.

あのやろう、逃げやがった。

Ano yarou, nige yagatta.

That bastard ran away.

Phrases

In addition to the various words that can be insulting, the following are some common phrases that might be heard during a fight.

ふざけんなよ。

Fuzakenna yo.

Don’t play around with me.

調子にのってんじゃねえぞ。

Choushi ni notten n ja nee zo.

Don’t get cocky.

しばくぞ、コラ。

Shibaku zo, kora.

Hey! I’m gonna hit you.

死ね。

Shine.

Die.

頭おかしいんじゃないの?

Atama okashii n janai no?

Are you crazy?

Other Aspects of Japanese Insults

In general, you might notice that the insult words and phrases don’t have as strong of a meaning as insults in English. For this reason, there are actually more ways that the Japanese language can become rude or insulting, aside from the specific insults.

Breaking Social Conventions

Social conventions are an important part of Japanese culture. There are unsaid rules that people follow relating to hierarchy and social status.

From a young age, Japanese people are taught to respect elders, those who are of higher status in their social/work/school circles, among others. In all of these interactions, there are varying degrees of politeness, which are reflected even in the grammar.

Here is a glimpse into how Japanese social conventions work:

Assuming you are working for a traditional, large Japanese company, if you were talking to the CEO of your company, you would need to be extremely polite by using the appropriate honorific titles and forms of speech. However, if you were talking to a co-worker who joined the company one year before you, it’s important to be polite but not to the extent of talking to the CEO.

How does that relate to insults?

Because most people follow these rules, it is shocking and considered rude if broken. For example, if you’re in your twenties and called a middle-aged man on the street ジジー (rude way to say grandpa) it would be an insult.

In a normal situation, the middle-aged man is of higher status because they are a stranger and older than you.

No Keigo

When being insulting, keigo or the polite form of grammar, is often dropped. This goes with breaking social conventions.

Among adults, talking to strangers who are not considerably younger than you without using keigo can already be insulting in many situations.

Similarly to how there is a polite form, there is also a ruder form of talking. This kind of speech would use only informal language, and possibly command form verbs like 死ね (die), だまれ (shut-up), 言え (say), 来い (come).

Calling people without honorifics

With the dropping of keigo, it can also be insulting to use no honorifics such as さん (san).

In Japanese society, it is not uncommon to at least use some form of honorific even with close friends. Although in some cases, it’s completely acceptable to call somebody without honorifics.

By dropping honorifics completely, it can be very rude and insulting as it also puts the other person at a lower status than you. Also, the insulting words for “you” can be used like おまえ or てめえ instead of the person’s name.

Not common to use insulting language

In English, it might be more accepted to use some insulting words as part of daily life to express yourself.

However, in Japanese, it is not usual to use that much insulting language. This is partly because breaking social conventions can already be quite offensive. The way you speak often matters more than the exact words you use. It can sound over-the-top or comical if insults are not used in the right context.

As many of these insults and phrases are commonly used by anime characters, it’s important to understand that anime can be an exaggerated version of reality. Be careful about actually using any of these insulting words or phrases and it’s best to observe how native speakers are using them first.

10 May 2020

All About Japanese Honorifics

(This article was reviewed and edited by native Japanese speakers to ensure accuracy.)

Honorifics represent the essence of Japanese societal structure. Getting a handle on how to navigate honorifics can not only make you a better Japanese speaker, but it will allow you to participate in the culture and society.

First, let’s dive into what honorifics mean in English:

Honorifics are titles that define a person to show their “status” and in English, it comes before a name. It could be titles such as Ms., Mrs., Mr., or Dr. In the case of royalty it could be “prince”, or in politics, it could be “president” or “senator”.

Although it’s also quite common in English, it’s not as prevalently used and complex as in the Japanese language. It’s increasingly common in everyday life to just refer to each other by first names.

So how does this work in Japanese?

In the Japanese language, honorifics appear at the ends of names and are used in a very conscious way.

Everyone can choose the level of politeness when speaking. Since many words and phrases have polite and informal forms, it makes sense that the honorific also plays a crucial role in showing politeness.

When not to use honorifics:

Before discussing the types of honorifics, it’s just as important to know when not to use honorifics. There is even a word called 呼び捨て(yobi sute) to mean no-honorifics. It can literally be translated as “to call and throw out”.

Generally, when using no-honorifics, it means that the other person is of equal or lower status than you. In Japanese, “status” can be determined by age and credentials. The exceptions are if the other person is extremely close, has given you permission to use no-honorifics, or is a family member.

Same age friends and classmates might call each other without honorifics. It is particularly common for men to use last names in these situations.

佐藤、今日暇?

Satou, kyou hima?

Satou, you free today?

Parents talking to their kids, family members who share last names, and small children talking among each other will often use no-honorifics with the first name.

カズマ、宿題やった?

Kazuma, shukudai yatta?

Kazuma, did you do your homework?

Teachers have the choice not to use honorifics to their students. Usually, it will be their last name without honorifics. (But teachers many also use honorifics. It’s their choice.)

佐藤、宿題やった?

Satou, shukudai yatta?

Satou, did you do your homework?

Another common situation is with sports coaches talking to members of their team. Usually, it will be without honorifics and called by their last name.

高橋、ボールをもっと高くキックしないとダメだ!

Takahashi, boru o motto takaku kikku shinaito dame da!

Takahashi, you have to kick the ball higher!

When talking to people from other companies, you should not use honorifics when referring to members of your own company. This applies even in situations where they are your boss.

This is because your boss is not the other company’s boss. In a sense, you must talk about yourself and your company as a lower “status” to show respect to the other company.

申し訳ございません。佐藤は今、席を外しております。(Satou is your boss.)

Moushiwake gozaimasen. Satou wa ima, seki o hazushiteorimasu.

I’m very sorry. Satou is away at the moment.

However, make sure to use honorifics when actually talking to your boss. In this case, 佐藤部長 (Sato buchou) if his title is 部長 (department head).

Types of honorifics

ちゃん – Chan

This is an endearing honorific that is used with children and friends. It is used with someone who is of equal or lower status.

It is generally perceived as a female honorific and has a kawaii, or cute, connotation. Depending on the context or situation, it can also apply to all ages and genders. This can sometimes make it difficult to understand the various uses.

It’s common to use this honorific when adults are talking to a child (normally girls) or among children. Parents might also use it with their children.

リナちゃん今日幼稚園どうだった?

Rina-chan kyou youchien dou datta?

Rina, how was preschool today?

Towards a close female friend or romantic partner, it’s also possible to use ちゃん.

サキちゃん、カフェ行かない?

Saki-chan, kafe ikanai?

Saki, do you want to go to a cafe?

This honorific also often combines with word stems that mean grandma, grandpa, uncle, etc… to show more endearment towards them. It’s similar to how in English we might say granny, gramps, auntie to be more affectionate.

おばあちゃん, おじいちゃん

Obaachan, Ojiichan

Grandma, Grandpa

おばちゃん、おじちゃん

Obachan, Ojichan

Aunt, Uncle

お姉ちゃん、お兄ちゃん

Oneechan, Oniichan

Sister, Brother

Also keep in mind that in Japanese culture, it’s possible to call a non-family member brother, uncle, aunt, etc… if you feel close enough. For example, you might call the middle-aged women from the corner store that you see almost everyday おばちゃん or auntie.

Situations when using ちゃん with a male might be if the other person is a close friend, family, romantic partner, or sometimes a child who is a boy. In these situations, it acts more like a nickname and the first name is often shortened to two syllables.

昨日カズちゃん勉強した?

Kinou Kazu chan benkyou shita?

Did you study yesterday?

くん – Kun

This is basically like ちゃん, but is perceived as a male honorific. It can be used informally towards those who are lower or equal in status, age, and qualifications. It adds more friendliness and familiarity to a name.

It’s often used when an adult or another child is talking to a boy. Parents might also use it with their children.

カズマくん宿題やった?

Kazuma kun shukudai yatta?

Kazuma did you do your homework?

With male friends, classmates, and romantic partners, it’s also common to use くん.

Among classmates, the last name is frequently used with くん. Keep in mind that there are many choices when it comes to the honorifics and it depends on your preference and the social group that you belong to.

佐藤くん、今度映画行かない?

Satou kun, kondo eiga ikanai?

Satou kun, do you want to go to the movies next time?

In business contexts, although a bit old-fashioned, it can be used towards subordinates using their last name. In these situations, it can also apply to women.

佐藤くん、プレゼンの準備できた?

Sato kun, purezen no junbi dekita?

Sato, did you finish preparing the presentation?

さん – San

This is one of the most frequent honorifics and a safe choice for most occasions. It’s polite and formal, but also friendly. It can be used with friends, as well as those who you’re not familiar with.

さん typically implies that you perceive the other person as being of a higher status, but it’s perfectly normal to use it with people of equal or lower statuses.

Especially when talking with strangers, it is a good idea to call them by their last name with さん to be more polite.

For example, if you’re calling someone you have never met on the phone (Mr. Tanaka) you might say: